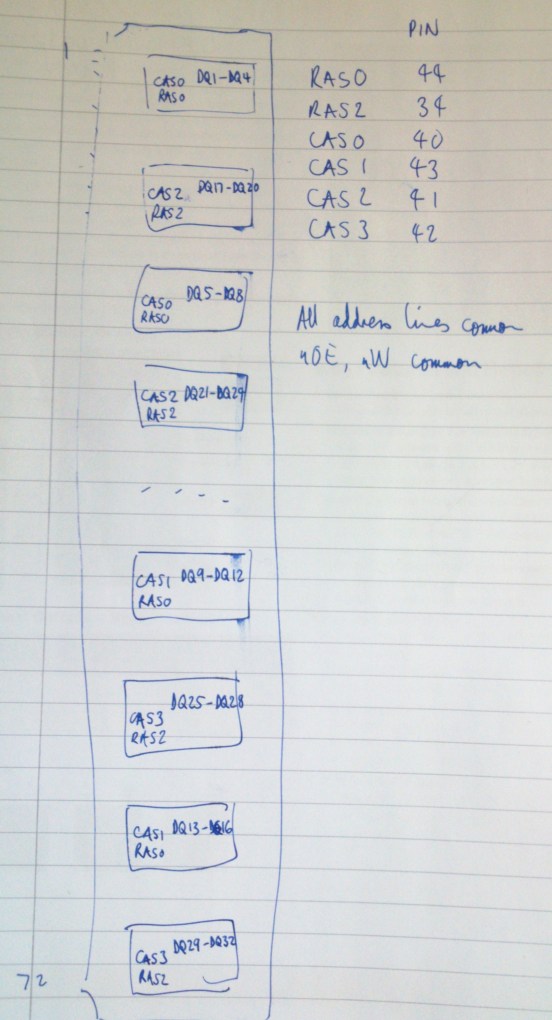

Having worked out the wiring for a 4MB SIMM to the 16500A CPU board in part 3, I got out the mod wire and soldered it all together.

It all went together quite easily. The pins, even on the SIMM, are so much further apart than modern surface-mount components that I’m used to dealing with. Notice the red wire running along the row of chips on the SIMM: that’s nOE, where I had to lift pin 16 of each chip and wire them together because the original SIMM tracks grounded them. I also cut the track joining all the pin 3’s (nWE) of the chips together, half way along the SIMM, so that the upper four chips had a separate nWE from the lower four, again because that’s the way the CPU board expected them.

Having checked and double-checked the wiring, I plugged the board into the mainframe and switched on. Much to my amazement, I heard the sound of the floppy drives seeking almost immediately. It was running! Once the monitor had warmed up, I could see that the mainframe was booting absolutely normally. It passed all its self-tests. But, did it recognise the extra memory? With some trepidation I stabbed the screen to select test mode and looked at the bottom line of the display:

Oh dear. Just 1MB then. Serves me right for trying to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. I suspect ROM version 00.00 (what kind of a version number is that?) doesn’t support more than this, since later 16500As had a different ROM version and more memory. Just for kicks, I popped in the test disk and tried the proper memory test:

At least the new RAM works as well as the old stuff did, even if it isn’t any bigger. I haven’t broken it, but I haven’t improved it either. I also tried loading the 16550A module software, just in case it was somehow able to find the extra RAM even if the rest of the system didn’t know about it, but it still reported that there wasn’t enough space.

I think my next quest will be to find a copy of the later ROM and program a couple of EPROMs with it. A quick Google search for ‘16500A ROM’ reveals this site:

http://www.jammarcade.net/hp-16500a-logic-analyser/

with an image of the later ROMs. When I get a moment, I’ll program up a pair of 27C256As and see what happens…